By John Henry (Hammered Out Homebrew)

Tabletop role-playing games (TTRPGs) offer players and Game Masters (GMs) a vast array of creative possibilities, from epic quests in fantastical realms to tense negotiations in futuristic cityscapes. The approach people take to structuring these games often take two different forms. These forms are the railroad and the sandbox. There are benefits and failings to both approaches. Looking online these days, you might find people ranting (shocker, I know) about the negatives of one approach versus the other. I’d like to talk today about these approaches and how both have their place at the table.

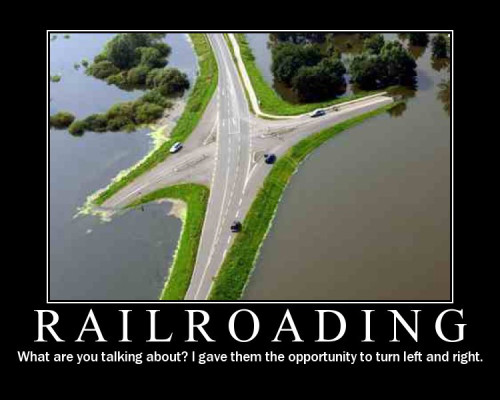

The Railroad Approach:

First, let’s talk about the Railroad approach. This approach is typically defined by the GM designing a linear narrative with predetermined plot points and encounters, akin to laying down railroad tracks for the players to follow.. The GM guides the players through a series of steps, leading them towards a predetermined conclusion. This method provides a clear direction for the story, ensuring a focused and cohesive experience

Advantages of the Railroad Approach:

Narrative Control: The GM has greater control over the story’s pacing, tone, and dramatic beats, ensuring a more cinematic and structured experience.

Immersive Storytelling: Players are drawn into a carefully crafted narrative, with opportunities for dramatic reveals, plot twists, and character development.

Streamlined Gameplay: With a linear progression, sessions are often more streamlined, allowing for smoother gameplay and fewer distractions.

Accessibility: The Railroad approach can be more accessible for novice players, providing clear objectives and direction.

Disadvantages of the Railroad Approach:

Narrative Burden: This approach places a lot of weight upon the GM. They are much more responsible for the way the story goes. This can lead to burnout (stress causing lack of enthusiasm and a desire to stop playing).

Player Apathy: Players can potentially feel like their characters do not matter in the grand scheme of things, that the only thing that matters is the GM’s story.

Unexpected Stops: With a clear narrative in mind, it can be possible for players to stump the GM or vice versa. This can make a stop to the story and lead to frustration if the communication between the players and the Gm is not ideal.

The Railroad approach may be best suited for story-driven campaigns with a clear beginning, middle, and end, one-shot adventures or short campaigns with limited time for exploration, and groups with novice players who may benefit from a more guided experience. If you are under a bit of a time crunch, for example, when you know people will be unavailable or you only want this particular adventure to last a certain number of sessions, this style can be ideal. The problems with this style mainly arise when there is not enough communication between the GM or preparation.

The burden can be reduced on the GM if they work with the players beforehand to establish tone and what everyone wants out of this story. On the player’s part this usually means going to extensive lengths to prepare their characters. If the GM knows the player’s characters like the back of their own hand, and trusts the players to stick with those character traits and flaws, they can create rails for the adventure based off of the expected character actions instead of their own detached story beats. This second one is how prewritten official adventures are written, which can be when the flaws of that approach are shown. This would also go a long way to alleviating player apathy and prevent unexpected stops. All of that takes time to plan out and prepare on both the GM’s and players’ parts, so let’s get into the approach that does not have that failing.

The Sandbox Approach:

Conversely, the Sandbox approach offers players a greater degree of freedom and agency within the game world. Instead of a linear storyline, the GM presents an open-ended setting filled with diverse locations, factions, and plot hooks, allowing players to explore and interact with the world as they see fit. They may have their preferred path but there are as many paths as the players can think of.

Advantages of the Sandbox Approach:

Player Agency: Players have the freedom to pursue their own goals, make meaningful choices, and shape the direction of the game through their actions.

Exploration and Discovery: The open world encourages exploration and discovery, with opportunities for unexpected encounters, hidden treasures, and emergent gameplay.

Dynamic Worldbuilding: The GM can focus on creating a rich and dynamic setting, with interconnected NPCs, factions, and storylines that react to player decisions.

Flexibility: The Sandbox approach accommodates a wide range of playstyles and character motivations, allowing for more diverse and personalized experiences.

Disadvantages of the Sandbox Approach:

Meandering: Without a clear direction it is very easy for players (and the GM) to not make any progress in the game. It’s possible for the game to be fine for the players with this going on (if they are more into the RP) but might be unsatisfying for more focused players.

No End: Without a set story in mind, it can be easy for the game to continue without a definable end. This might let a game stumble on past its time or ensure that a character never has an end to their story.

The unexpected: With a sandbox setting, the players can go in any direction. This can be a little daunting to a GM if they haven’t prepared that direction.

Unexpected End: Treating the world as its own thing without consideration for the relative power levels of the characters means there is a chance that they encounter something above their pay grade. A sudden end can be unsatisfying. Or, it can be fine depending on the group.

The sandbox approach lets the players be free and allows their actions to direct the direction of the game in multiple ways. This approach can also be easier for quicker pick up games if you are using a prebuilt world (our own or published). The problems that arise from this style stem from the open nature of this game. With no direction besides what they create for themselves, many players will freeze up a little and have a hard time deciding what to pursue. This can be a drag on fun and time. More experienced players typically take to this type of game easier since they are more confident in their decisions and what they can do.

The other aspect of this game is that it’s easier for the game to continue on past its natural end or for characters to never find an end. This is more of a social issue and once again requires communication between players and the GM on both aspects.

Choosing the Right Approach:

Deciding between the Railroad and Sandbox approaches depends on several factors, including the preferences of the players, the style of the campaign, and the experience level of the group. It may be easier for experienced players to jump into a sandbox, whereas new players need a guard rail before jumping off themselves.

If the campaign is heavily story based, then the rails might be preferred. Keep the failings of the railroad approach in mind and build the plot points or hooks at least partially around the player characters themselves. If your players just want to bash about the world (become murder hobos) then a sandbox is a great time for them. Most importantly, keep the player’s preferences in mind. RP and story focused players might not thrive in a sandbox unless they find just the right direction. Players that are more interested in other aspects of the game or wish to “steer the ship” might not be the best fit for a railroaded game.

Also, as a GM, keep your own preferences in mind. If you are more comfortable with one approach than the other, let players know. Communication is key and the conversation about what you want is better than trying to twist one game into the other or have small bits of resentment tinge how you run the game.

Finally, be aware of the schedule you have. If you want to play a game but know the time frame to play it is short, decide whether or not you have enough time to build the rails along with your players beforehand. A tightly structured game built with the players and the characters in mind can flow quickly and fantastically. If you don’t have the time to plan ahead, then dropping your players in a world and letting them go nuts is also fine for a session. There is also no rule saying one game has to stay one way forever. If what you and your players discover in the sandbox starts to feel like a solid story to come, you can start to build rails in that sandbox. If that’s truly what is wanted, be sure to communicate so that effort doesn’t go to waste. It’s also fine to build a couple rails in the sandbox for players to find if they wish. Additionally, after the plot is wrapped up in the railroaded game, maybe let the characters run amok in that world before leaving it.

What you decide to do is ultimately up to you. I, personally, start games off in a sandbox, but build characters with them. I start off with a general sandbox and let the players decide where to go at first. As the sessions go by, I think of a few plot hooks based off of those characters and weave them into the supports of the sandbox (world).

If the players bite on those plot hooks, I start laying down tracks along a plot based on what I think those characters would do in that situation, not just what I want to happen. Railroads do have junction points. There are decision points where a plot can take a certain turn. There will be times I am surprised and I can start laying down new tracks based on that decision since I was there for my players making their characters and have a rough idea of what they want to do.

Typically in long games, I plan these railroads out for 5-12 sessions, with the idea to let the players return to the sandbox between these tracks. We then assess what we all want from the game. Some serious sandbox time, another railroad, or to completely stop with that game and start the process all over again.

Good luck and remember to communicate with your players!

About the Author

John’s TTRPG experience: He has played D&D off and on for 14ish years. Starting in 2019, he has consistently run campaigns and one shots. Starting soon after that John started publishing his homebrew to the internet. He has written enough homebrew that he has plans for a book of it to be released sometime in 2023(DrivethruRPG). He has also played Monster of the Week, many RP board games, Call of Cthulu, and Pathfinder. You can see other of his work on Instagram!

Leave a comment