By: Joe Gaylord (Lazarus Game Lab)

Running a horror TTRPG is a huge lift for a GM.

This is true whether you’re playing a primarily horror focused game, like Call of Cthulhu or Dread, or a horror adventure in a more generic TTRPG, like D&D games set in Ravenloft.

Running horror games presents all of the typical challenges of GMing: providing a compelling game, tracking statuses and mechanics, recalling the events of the world, keeping players on track, and dictating the game actions for everything outside of the PCs. However, horror games add to this complexity by asking the GM to not only tell a compelling story, but one that is genuinely scary.

This is a task that’s hard enough when we have full latitude to shape the story, the way that traditional authors do. It feels near impossible when constrained by game mechanics and needing to adapt to the needs and actions of others. However, language is a good way to start.

Language is the ideal starting place to make a game genuinely scary. TTRPGs exist primarily as language, and telling and listening to scary stories is also a fundamental human experience. It harkens back to when our ancestors sat around fires, talking about real monsters that lurked in the dark. So, let’s unpack the language of horror, and use it to make our horror games better.

A Dark and Stormy Night

You know how a scary story sounds. Among literary genres, horror has an extraordinary number of conceits and tropes. Fear has a specific language and style that you can use to your advantage in a horror TTRPG.

Each horror subgenre has its own set of vocabulary. Slashers creep in the shadows, with momentary flashes of the villain and fake jump scares as heroes search for them. Gothic villains sit in grand castles, surrounded by ancient wealth or arcane instruments, looking haughtily down at their foes. Cosmic horror is punctuated by surreal creatures and images that defy understanding. When you’re preparing a horror TTRPG, decide on your subgenre then seek out stories and films from it to get comfortable with the vocabulary of that genre.

Once you’re comfortable with that language, lean into that. Because horror is so closely tied to specific vocabulary, your players are primed to associate that vocabulary with feelings of fear. It’s trite, but if you describe a group of young people splitting up to investigate the noises coming from the basement, a looming castle with lightning flashing behind it, or a strangely colored meteor falling onto a farm, your players will know something bad is about to happen. Those associations can bear some of the load of making a game scary for you, effectively letting you co-write with John Carpenter, Bram Stoker, or HP Lovecraft. Tropes exist because they work. Use them.

Or don’t. Subverting tropes is also an effective tool. Taking something that is set up to be scary and having it turn out harmless or having a threat emerge unheralded by tropey language can keep your players uncertain about the nature of the horror they face. Horror often hinges on not knowing what comes next as much as on setting up expectations. This works best when those expectations are very clear. A story that subverts tropes at every turn can come off as simply confusing, but one that relies on tropes until the perfect moment to strike is much more effective. If the looming castle is actually a themed restaurant and the real monster has been the friendly neighbor helping the kids all along, that probably works. If the castle is actually a bounce house, the menacing monster is actually a squirrel, and the vampire only drinks grape juice… That risks coming off as comedy, not horror.

Whether leaning in or subverting, knowing your way around the horror tropes is a building block of telling scarier stories.

Varying Kinds of Fear

Though they are often used in the same way, it’s worth noting the difference between horror, terror, dread, suspense, and revulsion. All of these are kinds of fear, but they work in different ways that are instructive for horror TTRPGs and stories.

Dread is a general feeling of fear or tension. The source is atmospheric. There usually isn’t a specific thing you’re afraid of, just a situation, setting, or circumstance. Dread often relies on a strong sense of setting and mood, such as wandering into a foggy moorland at night or hearing a mysterious sound as you explore a dungeon.

Terror is a fear of a known, but remote or theoretical, event or evil. The thing you’re afraid of is specific, but it’s distant, hidden, or not fully real yet. Setting up terror requires limited information and distance, the zombies that will rise at sunset or the rumors of a ghost in a haunted house don’t give details, but provide the basis for fear.

Suspense is fear of an uncertain outcome. The negative result may not be specific, but the situation could go badly in ways that are frightening. An example of increasing suspense working with very specific images or events such as a slowly opening door or a race to escape a vampire before sunrise…

Horror is the fear of a specific image or event. You are presented with something that is aberrant or frightening and it creates fear in you. This often relies on clear imagery or detail, such as stumbling on the killer’s last victim or seeing a possessed child’s eyes glow red.

Finally, revulsion is a more visceral reaction to a specific image. It goes beyond horror because the reaction is more physical than psychological. As such, it still makes use of imagery, but tends to have more detail and less atmosphere, such as seeing a ghoul eating the intestines of a fallen horse or witnessing a killer chop a victim’s head off.

For every kind of fear, but especially for revulsion, it’s essential to be careful. This is a game and it’s meant to be fun. That fun can include making ourselves afraid, but when we do that we can get close to a line. It’s easy for “fun fear” to slip into psychological trauma for the players, not the characters. There are excellent safety tools out there to avoid this. Stoplight checklists, lines and veils, and X cards are some that I encourage you to look up and use at your table for horror themed games. A great starting place is here: https://ttrpgsafetytoolkit.com/

One narrative will often use all of these in varying ways. Think of a werewolf story.

1. A traveller enters a village and there is a sense of unease, maybe noises in the forest or a feeling of being hunted. This is dread.

2. The same traveller stumbles on the body of a child torn apart by the creature, without context. This is revulsion.

3. They are arrested on suspicion of being the killer, and told about rumors of a creature in the forest, they hear howling in the woods, and fear a villager is a werewolf. This is terror.

4. They enter the forest one night, their horse is spooked and flees, and they have to run through the forest to escape something that is chasing them. This is suspense.

5. Finally, they see the werewolf burst from the forest, and, as clouds pass over the moon, see the creature turn painfully into a human and back into a wolf-thing. This is horror.

All of that sounds abstract, and it is in a sense, but knowing the story beats and where on that spectrum you want a story beat, adventure, or overall encounter to fall will help you think about the tone and description you want to give as a GM.

In particular, it’s useful to think about the flow between these different kinds of fear. A good horror story is a process of tension and release. Dread, terror, and suspense build up tension. Horror and revulsion (and escape or safety) provide release. Too much tension feels like things are going nowhere, too much release lacks emotional weight. Horror and revulsion especially lose their impact and feel cheap if not set up well. Also, adding in moments of hope, peace, and humor can give players a break and give more weight to frightening moments by comparison. Varying the pace and rhythm helps to keep things scary while keeping the story moving.

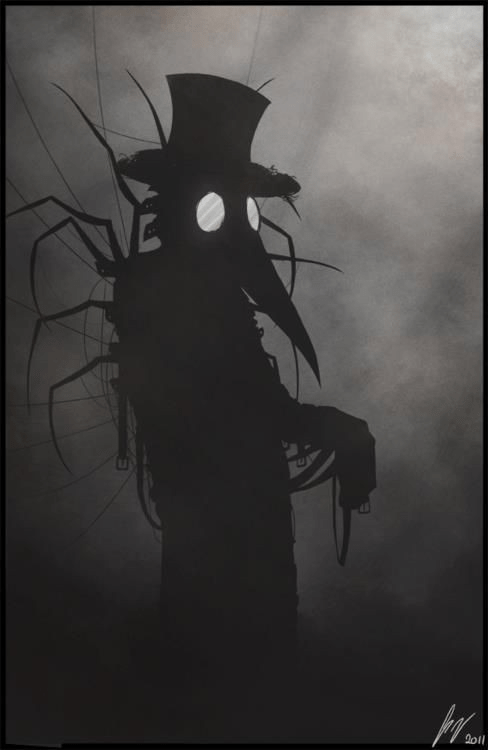

Don’t Show the Shark

“Don’t show the shark” is classic horror advice, and is well worth keeping in mind. It comes from the movie Jaws, which kept the monster shark at its center off screen or seen only in brief glimpses for nearly the whole film. The crux of the idea is that if you want something to be scary, make it less evident, keep your monster lurking in the shadows, hidden behind a mask, or known only from rumors.

This works because it keeps the danger mysterious. You can’t describe something as terrifying as your players can imagine. The more specific you are about the description the better your players can visualize and understand it, and if they understand it, they can rationalize and grasp how to deal with it.

A key tool in making this work is evocation, which Stephen King talked about in his book On Writing. Evocation is the art of providing just enough description to let a reader (or player) fill in the details, without describing everything in detail.

Another tool to keep dangers mysterious and threatening is to mix senses in novel ways. Describing something as looking like a migraine, feeling slick and red, or smelling like pain isn’t really useful for players trying to understand what they’re dealing with, but they provide specific and unsettling imagery that adds to a horror atmosphere.

Conclusion

Thinking closely about how we tell a scary story is a key tool to running an effective horror TTRPG. By carefully leaning into and subverting tropes, you can use players’ culture and experiences to build a scary atmosphere. By selecting and shifting between kinds of fear, you can build a scary atmosphere through cycles of tension and payoff. Finally, by keeping threats mysterious or poorly understood, you keep players off balance and afraid.

Language is what we have to build our worlds in TTRPGs. The more you learn to use it to shape the style or atmosphere you want to create, the better you will be as a GM, and the better, and scarier, your games will be.

About the Author

Joseph Gaylord has been playing TTRPGs and TCGs for 25 years, with almost 50 titles to his name on DMsGuild as an author, co-author, or contributor. He is on most social media as LabLazarus.

Leave a comment